Jeff Gudman, the Republican candidate for Oregon Treasurer this fall, was listening in on Friday’s meeting.

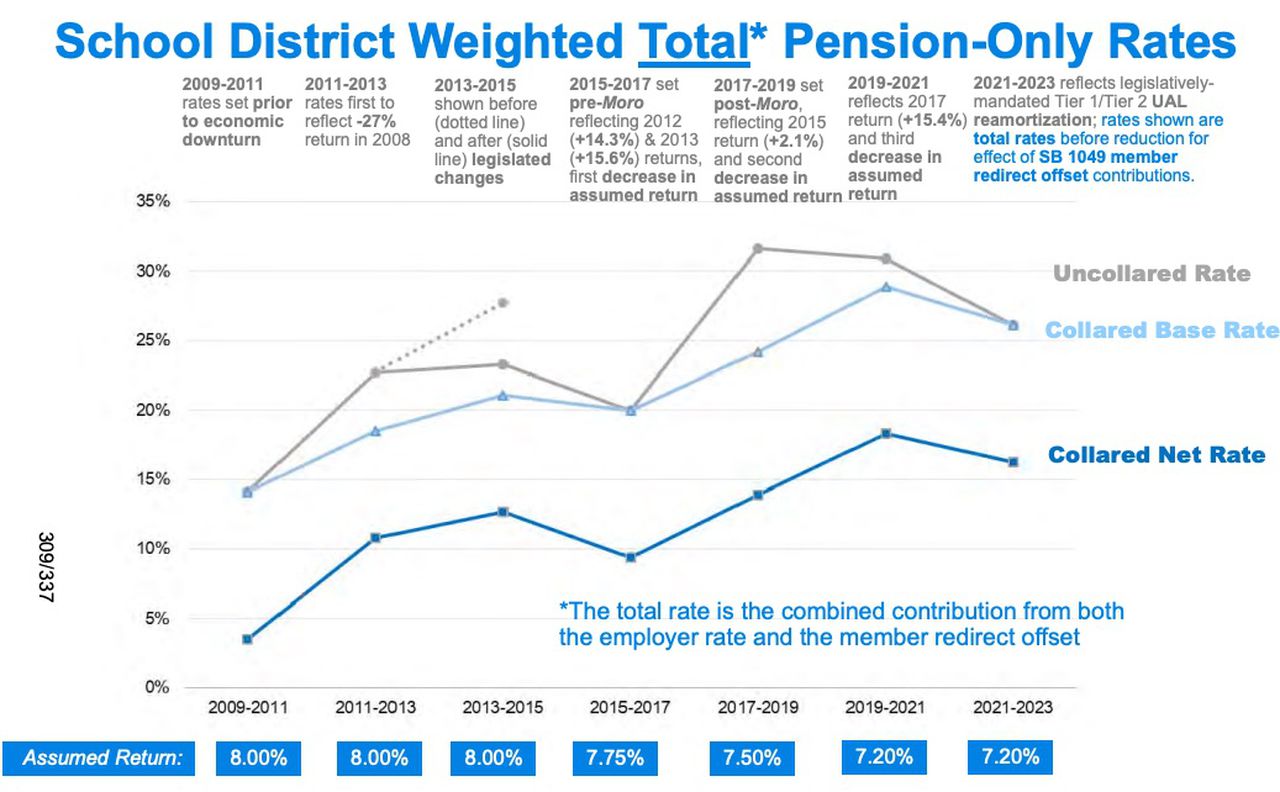

This graph shows the trend in pension contribution rates for school districts in Oregon. Statewide, the average contribution rate for all public employers is somewhat higher, though shows similar trends.

Oregon lawmakers have successfully, if perhaps temporarily, halted the steady upward trajectory of public pension costs for government employers, according to a preliminary analysis of pension contribution rates that will kick in a year from now.

That’s good news for public employers around the state struggling with revenue declines amid an economic recession, and increased service needs to combat the ongoing coronavirus pandemic.

Yet the rate relief comes at a precarious time for the pension system’s already troubled funded status. It also raises question about the wisdom of lawmakers’ moves when it comes to assuring the system’s long-term health.

Milliman Inc., the system’s actuary, presented the board of Oregon’s Public Employees Retirement System with the results of its preliminary system valuation on Friday. The study analyzed the system’s financial condition at the end of 2019. A final version due in October will be used to set public employers’ required pension payments in the two-year budget cycle that begins next July.

Those required payments have been on a steady upward march in the aftermath of the 2008 recession as the board attempts to dig out of a funding deficit that now stands at $24.5 billion.

The rising payments have put increasing pressure on the budgets of schools, state agencies, municipalities and other public employers across the state. But due to unsteady investment returns, they have done little to improve the financial status of the pension fund, which now has 72 cents in assets for every dollar in liabilities.

Nevertheless, lawmakers stepped in last year to provide employers with some budget relief. In particular, Gov. Kate Brown was determined to halt pension cost increases for schools and assure that revenues from the state’s new business tax for education made it into classrooms, and wasn’t siphoned off to pay increased pension costs.

Lawmakers engineered most of the savings with an accounting trick: extending the repayment period for the pension deficit for a decade. Senate Bill 1049, passed in 2019, also required public employees making more than $30,000 a year to resume making contributions to the system, which will offset a small portion of employers’ costs if they survive an ongoing court challenge.

The legislation had the desired effect. Milliman said Friday that employers’ average contribution rates to the system, which are expressed as a percentage of their payroll, would decline slightly next July, from 18.32% to 17.93%.

But in some ways, the situation looks analogous to 2009, when the PERS Board slashed employers’ contribution rates based on the system’s healthy financial status at the end of 2007, after a six-year run of robust investment returns. By that time, however, PERS had already seen the market value of its investments implode. They dropped 27% in 2008, blowing a funding hole in the system that was only partially mitigated by strong investment returns the following year. After those lower rates went into effect, the system’s unfunded liability increased by 20% between 2009 and 2011.

The situation today is somewhat different. Financial markets have remained largely disconnected from economic fundamentals. The broad stock market, measured by the Russell 3000 index, is only down 4% from its record high in February, amid huge job losses and an economy that is struggling to recover amid a resurgence in the coronavirus.

Oregon’s pension investments were down only 4.5% year-to-date at the end of June. But the consultant charged with projecting investment returns for the state predicts that losses from the fund’s private equity and real estate holdings – about a third of the portfolio – will likely worsen over coming quarters as the valuation of those assets, which aren’t publicly traded, catch up with public markets.

The board also learned Friday that the consultant, Callan Inc., was lowering its 10-year projection of the fund’s investment returns from 7.3% to 7.1%. The number is another critical driver of employers’ required contributions. Despite pressure to lower its own assumption, the PERS Board decided a year ago to protect employers from further upward rate pressure by standing pat on its current investment return assumption of 7.2%. It won’t revisit that question for another year.

There’s no telling where financial markets go from here. But Milliman said Friday that if the fund finishes the year where it is today, the system’s unfunded liability would grow to as much as $32 billion, and its funded status would fall to 65 cents in assets for every dollar in liabilities.

Nancy Brewer, finance director for the City of Corvallis, listened in on PERS Board meeting Friday and was alarmed by what she heard. She remembers some of the decisions the PERS Board made in the late nineties, which ultimately opened up the yawning structural deficit the fund faces today. In light of the current economic situation, she feels the pension fund’s investment portfolio will be lucky to end 2020 where it stands today

“I worry that we’re making short term funding decisions, and we will look back at this and say coulda, shoulda, woulda,” she said.

Public employees have sued to overturn the provisions of Senate Bill 1049 that require employees making more than $30,000 to start making contributions to the pension fund. The law directs 2.5% of salary for employees hired on or before August 28, 2003 to support the pension fund, and 0.75% of salary for employees hired after that date. Those contributions are expected to save employers some $300 million statewide in the next budget cycle by directly offsetting a portion of their contributions.

There was some discussion at Friday’s meeting about what to do if the Oregon Supreme Court does overturn the employee cost sharing in the middle of biennium. Milliman had proposed that employers’ rates would immediately adjust upward to maintain the same overall level of contributions to the system, though board member Lawrence Furnstahl, chief financial officer at Oregon Health & Science University, expressed hesitation due to the potential mid-cycle hit to employers’ budgets.

Brewer, the finance manager for Corvallis, said she supports immediately raising employers’ rates if that comes to pass.

“Short-term rate reductions lead to long-term rate increases that are going to be higher and last longer,” she said.

Again, the situation parallels past events. In 2013, the Legislature passed a series of cuts to employee pension benefits to save employers money, including limits on retirees’ cost of living adjustments. Those savings eliminated sizeable projected increases in employers’ contribution rates in the next two-year budget cycle. But the Oregon Supreme Court overturned the changes in April 2015, calling them an unconstitutional breach of contract. Three months later, the PERS Board let the lower rates go into effect anyway, shortchanging the system for another two years and further exacerbating its funding problem.

Gov. Brown on Friday called a special session of the Legislature for lawmakers to close a projected $1 billion shortfall. PERS staff told board members that the Legislature’s budget chiefs were considering eliminating some of the relatively anemic provisions in Senate Bill 1049 that were actually designed to improve the system’s unfunded liability. One proposal would sweep dollars appropriated to an incentive fund designed to encourage employers to make extra contributions to the pension fund, and abolish future revenue streams dedicated to it. Another would sweep money back to the general fund from another fund established to reduce schools’ future pension costs.

Jeff Gudman, the Republican candidate for Oregon Treasurer this fall, was listening in on Friday’s meeting. Given the presentation to the board, he said consideration should be given to accelerating the timing of any projected rate increases, despite the pain it in till inflict on every level of government and residents.

“Paying later will be even more painful,” he said.

— Ted Sickinger; tsickinger@oregonian.com; 503-221—8505; @tedsickinger